Huawei runs a little-known corporate VC division called Habo Investment. I first wrote about Habo back in early 2021, when it was barely two years old. Yet, at that time, it had already made 22 investments, five of which have gone public on the Shanghai STAR market– rather prolific from an investment-to-IPO perspective.

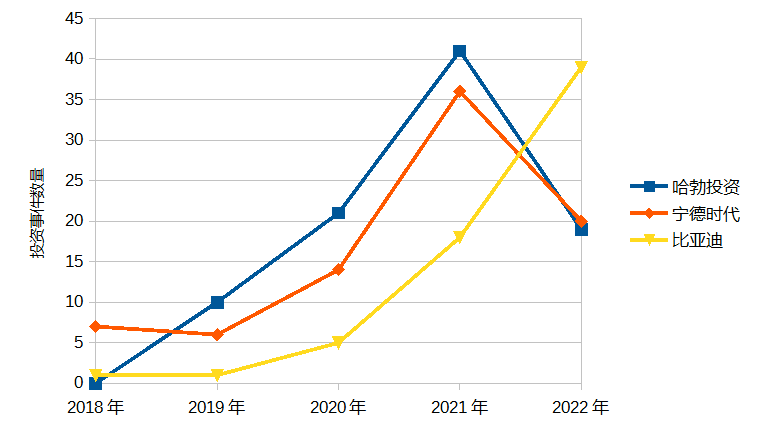

Habo has only gotten busier since. And not only Habo, but also the corporate venture arms of two other “national champions” – CATL and BYD. Here’s a chart of Huawei, CATL, and BYD’s respective corporate VCs’ deal volume in the last five years, courtesy of CVSource. Since 2018, Habo (blue) has made 90+ investments, CATL (orange) has made 80+, and BYD (yellow) has made 65+. The pace of investment from all three has picked up since 2020 and has continued unabated.

Unsurprisingly, the investment targets work on different layers of the supply chains that these three behemoths care most about. Habo invests in the semiconductor supply chain – from chip design to wafer manufacturing. CATL and BYD invest in different areas of the lithium-ion battery supply chain and startups working on advanced manufacturing or new materials. Again, unsurprisingly, these are all sectors that are of growing national strategic importance, as China shifts its technology innovation and self-reliance agenda to “hardtech” industries. All three are increasingly willing to write checks for early-stage, less proven startups – somewhat uncharacteristic of corporate VC practices.

For the young startups working in one of these “hardtech” industries, the appeal of an investment from a Habo or CATL or BYD is obvious. To make a “hardtech” startup successful, money alone isn’t enough. And there are no marketing tricks or product-led growth hacks to get you to the promised land of product-market-fit. A check from an established and motivated corporate VC gives these “hardtech” startups the trifecta of:

- Capital

- Stamp of approval from an incumbent giant

- A stack of purchase orders for your unproven-but-promising product

The corporate balance sheets of these “national champions” are becoming the engine to underwrite and bankroll strategic national priorities (and make some nice returns in the process). This trend also marks a changing of the guards from Alibaba and Tencent in China’s corporate VC landscape.

End of Team Ali vs Team Tencent

A startup’s golden ticket to fame and fortune used to be a check from either Alibaba or Tencent. During China’s Internet boom, you are either on “Team Ali” or “Team Tencent.” With that affiliation comes either the massive platform advantage on Taobao or AliPay that Alibaba offers, or the massive traffic and distribution advantage on WeChat that Tencent offers. This dynamic has produced many epic, money-burning battles between the two camps. Some of them eventually ended in truce that benefited all, e.g. the Meituan-Dianping merger and the Didi-Kuaidi merger. Others left mountains of waste, no clear winner, and continue to this day, e.g. bike-sharing competition between Mobike, Hellobike, etc.

Up until 2018, more than 50% of China’s tech unicorns are still either with Team Ali or Team Tencent. With a slowing economy, Covid, tougher antitrust and data regulations, intensifying technology sanctions from the US, and the central government’s broad effort to clean up 40 years of “startup debt” since Opening and Reform (a topic I explored in-depth before), being in either Alibaba or Tencent’s orbit is not what it used to be, as both giants try to “look smaller.”

Tencent has been actively divesting its winning investments, like JD and Meituan. Alibaba has broken itself up into six divisions, where each one (except for the China Commerce division) can raise outside capital and IPO if ready; instead of continuing to be an investor, Alibaba’s trying to become an attractive investee! (See more of my thoughts on the Alibaba reorg here.)

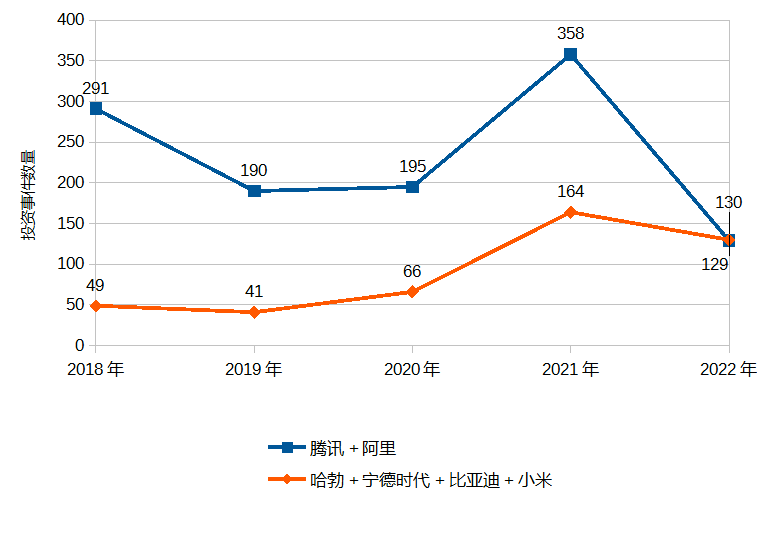

Alibaba and Tencent’s combined investment deal volume (blue) has fallen to about the same level as the combined volume of Habo, CATL, BYD, and Xiaomi (orange). (The smartphone maker is another active corporate VC in the “hardtech” realm, though it has investments in Internet companies too.)

While I don’t see Alibaba or Tencent stop making investments altogether, the changing of the guards in the corporate VC space seems apparent, as China shifts its strategic priorities into sectors where neither tech giant has a natural advantage in.

Instead of Team Ali or Team Tencent, it’s more beneficial to be on Team Habo or Team CATL, though at the end of the day, everyone must be on Team China. This leaves traditional VCs in a tough spot.

Traditional VCs Getting Squeezed

One fascinating element of the US-China technology relationship is how similar are the traditional venture capitalist firms that operate in both markets. The tech VC communities on both sides have similar information flow, display similar risk appetite, bet on similar trends, and oftentimes even have similar LPs. (This similarity is well-documented in Sebastian Mallaby’s book on the history of venture capital, “The Power Law”.)

Despite co-existing with the Alibaba-Tencent kingmaker duopoly in the last decade, VCs in China have done well, whether they are ones with an American brand (Sequoia China, Matrix China, etc.) or purely homegrown outfits (Hillhouse, Qiming, Source Code, many more). However, the next decade may prove to be lean years as these traditional VCs get squeezed by both the “hardtech” corporate VCs and geopolitical complications.

On one side, traditional VCs have almost no technical knowledge advantage compared to industry incumbents. Furthermore, they cannot offer much in terms of supporting business growth to lure startups to take their money, no matter how strong their network or business development team is. As one semiconductor-focused investor lamented in this article, “No matter how persuasive we are, there is no way we can throw purchase orders in front of [a startup].” But CATL can. BYD can. Habo surely can. Of course, VCs can still invest alongside or after these corporate VCs (and many already do to adapt to this new environment), but the entry price, exit option, and return prospect are all generally worse.

On the other side, almost all the “hardtech” sectors fall into categories that are geopolitically sensitive and will likely trigger new US government scrutiny. This squeeze is less of an issue for VCs in China with only Chinese LPs, but is shaping up to be a major problem for firms with US LPs. There is a growing worry in Washington that American money is being deployed via VC firms to fund Chinese technology advances. There is also an appetite to stop this inadvertent support of an adversary; President Biden may sign an executive order to this effect later this month. Sequoia China has hired a DC-based national security advisory firm, Beacon Global Strategies, to try to stay ahead of this risk. I have heard other VC firms hiring similar geopolitical risk firms to do the same. If this risk becomes reality, the problem won’t just be a bad entry price, it will be no entry at all.

The pain and suffering of venture capitalists is, of course, the least of China’s concerns. The road to self reliance up and down the technology supply chain stack is long and arduous. To make that road a little less long, investments from “hardtech” corporate VCs will play an increasingly larger role.