India is becoming an increasingly influential player in the ongoing technology conflict and competition between the U.S. and China -- from its border conflict with China (dating back to the 1960s), to the banning of all apps made by Chinese tech companies, to some Indian entrepreneurs promising to never take Chinese money as investments. Meanwhile, American tech companies and tech-focused investment firms (Amazon, Facebook, Silver Lake, Intel, Sequoia India, Walmart, Google) are pumping money into India’s tech sector at a rapid pace, though mostly concentrated in Jio.

While India’s recent actions certainly play into the larger narrative of decoupling, there is way more entanglement that meets the eye, especially when you look at the threads of money that interconnect the tech industries between these three countries.

To explore this tension between “decoupling” and “entanglement”, let’s look at the corporate strategic investments made by large American and Chinese tech companies in Indian “unicorns” (tech companies with a private market valuation of 1 billion USD or more). I choose to look at “corporate strategic investments” only, because these types of investments are typically only made if there is a tight long-term business alignment between the corporate investors and the invested companies, thus a strong signal of entanglement. That’s not to say there’s no alignment for a venture capital, private equity or sovereign wealth fund investment; the signal is just weaker.

Of course, India’s large and complex economy is more than just its tech unicorns. I’m focusing on them, because they do tend to be a leading indicator of where an economy’s tech sector is headed. There are also enough Indian unicorns now -- 21 total -- to actually analyze; this analysis would not have been possible five years ago.

Breaking Down the Entanglement

Before breaking down these corporate strategic investments in Indian unicorns, let’s spell out my sources of research first, so you know where these numbers came from. The Indian unicorns come from this continuously-maintained global unicorn list by CB Insights. The information on strategic investments come from CB Insights, Crunchbase, and various media reports about these companies. No proprietary information is disclosed in this post; you can reproduce everything by just Googling around.

Out of the 21 Indian tech unicorns, more than half have taken strategic investments from Chinese tech companies, about a third have taken similar investments from American companies, while a third have not taken money from either sources. What’s most interesting is that there are six unicorns who have attracted strategic investments from both American and Chinese companies, namely:

- One97 (owns Paytm) -- Investors: Alibaba/Ant Financials, Intel

- Oyo -- Investors: Didi Chuxing, Airbnb

- Snapdeal -- Investors: Alibaba, Intel, eBay

- Zomato -- Investors: Ant Financials, Apple

- PolicyBazaar -- Investors: Tencent, Intel

- Udaan -- Investors: Tencent, Microsoft

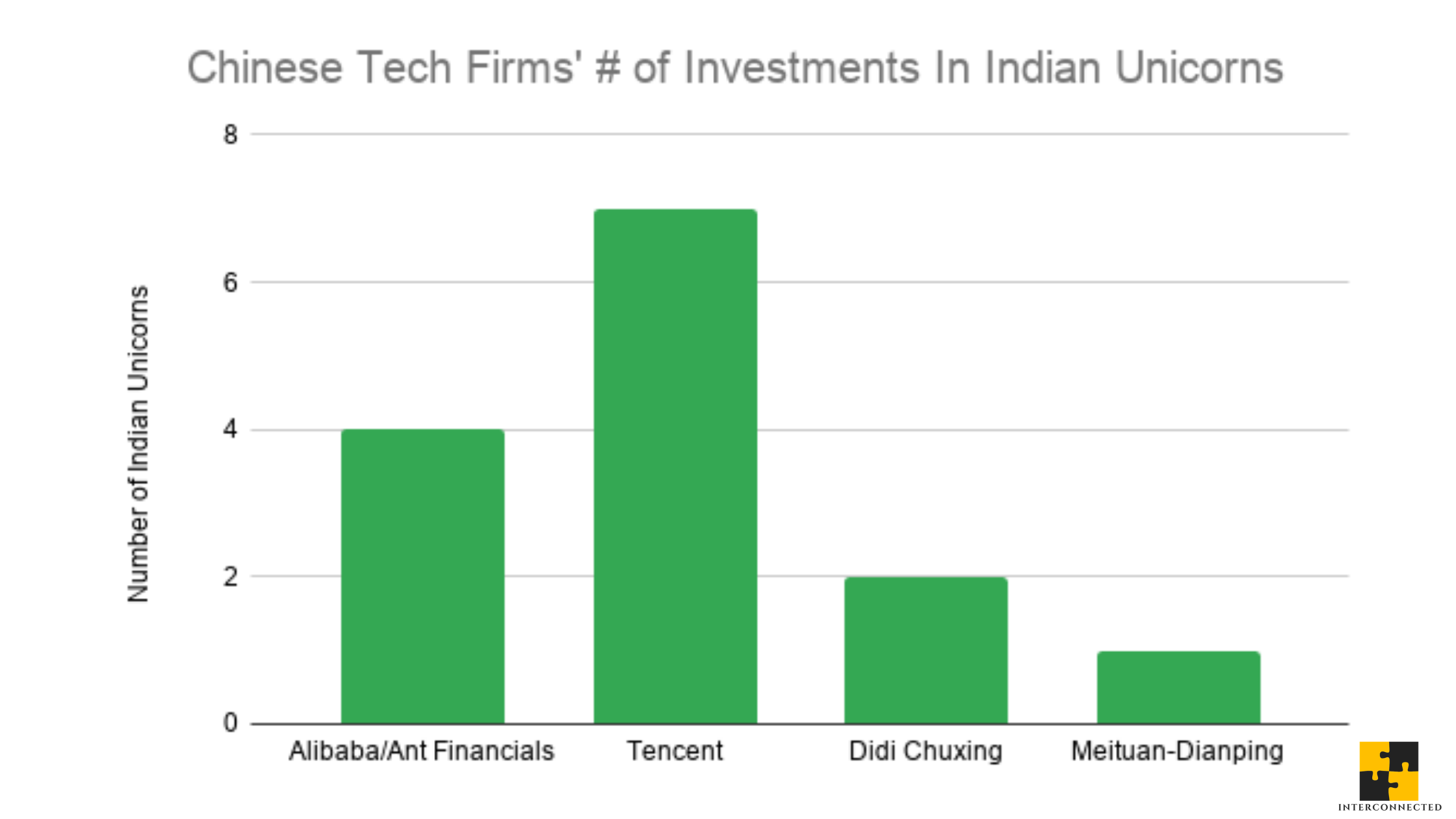

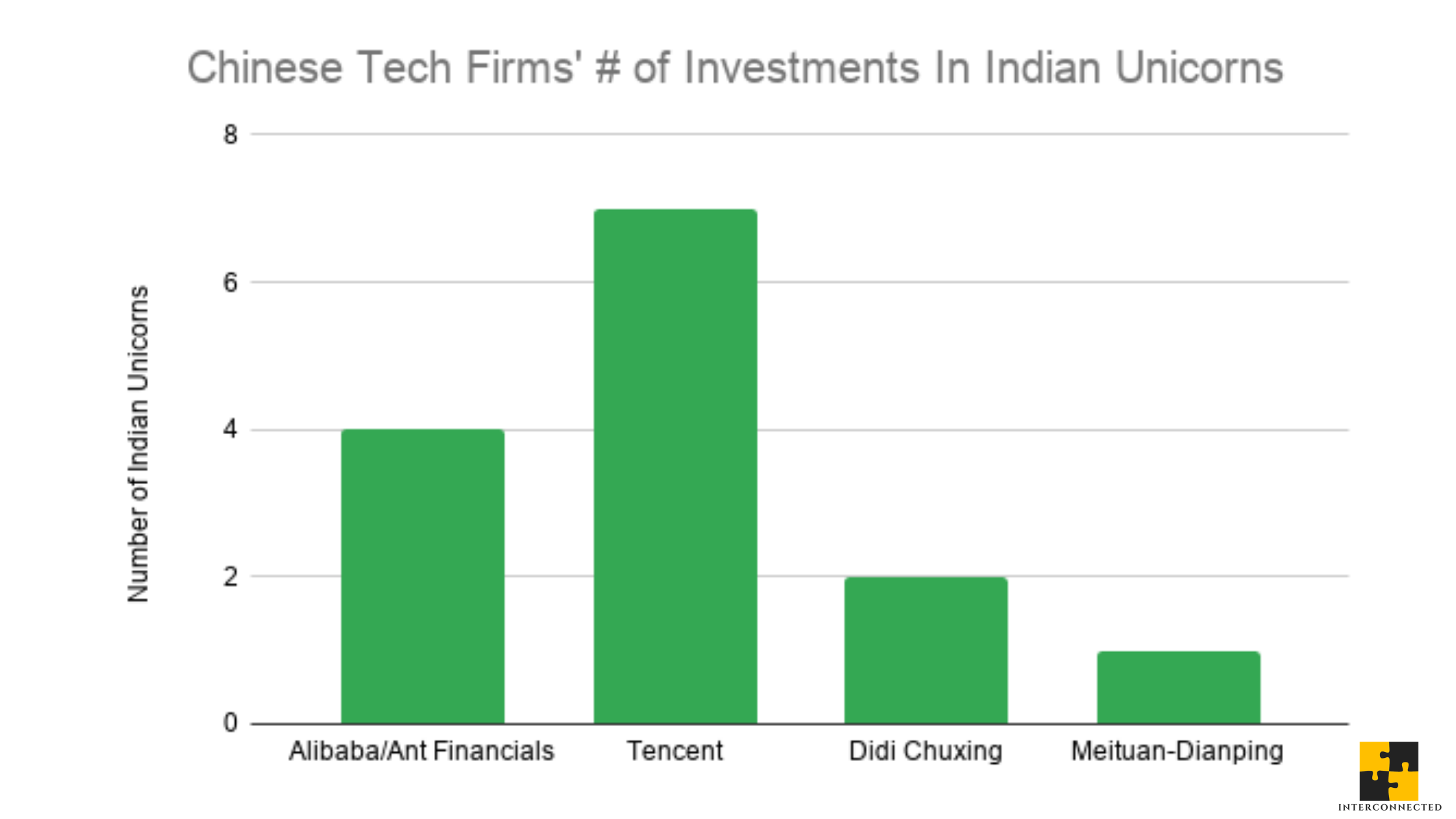

Since Chinese tech giants are invested in more than half of the Indian unicorns, I thought it’d be interesting to break down this group further. This chart breaks down the number of Indian unicorns each of these Chinese tech giants have made strategic investments in.

As any observer of the tech scene in China would know, the entire landscape is carved out into either Alibaba/Ant Financials territory or Tencent territory, manifested in aggressive strategic investments and proxy rivalries. The very existence of Didi Chuxing came out of a merger between Didi Dache (backed by Tencent) and Kuaidi Dache (backed by Alibaba) to mark a truce between the rivalry of these two giants in the ridesharing industry.

There is no evidence that India’s tech landscape is being carved out in quite the same way. And I’m sure the Indian tech community will resist that reality, especially given the current climate. But there is evidence that the proxy rivalry between Alibaba and Tencent is playing out in certain industries in India as well.

The best example is the fierce competition between Zomato (backed by Ant Financials, thus Alibaba) and Swiggy (backed by Tencent and Meituan-Dianping) in the food delivery business. The recent anti-China sentiment in India directly affected Zomato’s ability to access Ant’s investment, hurting its chances to compete with Swiggy. It’s worth noting that Uber sold its India food delivery service to Zomato in January for a 9.99% stake, so Uber also has skin in this rivalry. More broadly, Uber also sold its China operations to Didi Chuxing in 2016 for a 17.7% stake at that time, so it has vested interests in all of Didi’s investment activities in India as well. But Uber does not appear directly in the fundraising history of any of these Indian unicorns.

Much entanglement indeed.

Whose Money is “Smarter”?

There’s more to these investments than just the money wired from one account to another. It’s never just about the money, but more about the partnership and knowledge transfer from the successes and failures of the investors, which are arguably more valuable than the cash itself. It’s the so-called “smart” money, which becomes an especially important consideration when a company thinks about taking corporate strategic investments.

So is Chinese money “smarter” than American money when it comes to India? Looking at this breakdown by industry of the Indian unicorns, there is good reason to think that Indian entrepreneurs believe this is the case.

For several of the categories in this chart, Chinese tech companies are either the clear leaders in terms of innovation and technology (E-Commerce) or are operating in market conditions that are more analogous to India’s own situation (Logistics/Supply Chain and FinTech).

To double-click on FinTech for a moment, it’s not that there’s no innovation in the U.S.; in fact, plenty is happening in payment, loans, and insurance. But a lot of the innovation is built on the infrastructure and user behaviors around credit cards -- something that isn’t ingrained in either China or India. Thus, in China, the payment experience leapfrogged directly from dirty paper cash to digital cash, while other financial products are tied to the digital payment gateways, like AliPay and WeChat Pay, as well. It would make sense for India, whose Internet economy is roughly about where China’s was 10-15 years ago, to follow this path and add its own innovation to meet the needs and habits of Indian users. But it would not make sense for India to introduce a credit card system like America’s then innovate on top of that.

The “Others” catch-all category in the chart comprises a collection of industries: EdTech, AdTech, Gaming, Food Delivery, and Clean Energy. In all of these areas, it’s fair to say that the leading Chinese and American companies are competitively and comparably valuable to an Indian firm looking to grow and build in the same industries.

For the sake of focus and clarity, this post only looks at corporate strategic investors and purposely leaves out some of the other major investment players in India -- Softbank (Japan), Temasek (Singapore), Tiger Global, other private equity firms, and many many VC funds -- even though they are very much part of the entanglement. Even Berkshire Hathaway, famously allergic to investing in tech, is in the game with its $360 million USD investment in Paytm (India’s leading payment product), which entangles its interests and incentives with Alibaba/Ant Financials.

Personally, I support some level of “decoupling” for all countries. If the COVID-19 pandemic taught us anything, it’s that when it comes to running a country, a certain level of self-sufficiency and resource independence is absolutely necessary, if only to fulfill the basic duty of taking care of one’s own citizens.

But too much of the discussion around “decoupling” is binary and somewhat devoid of the current technology and business realities. (I recently explored the technology reality of global cloud computing in “Southeast Asia and the Pacific Light Cable Network”.) When it comes to the India-China-US trifecta, there’s clearly a lot to untangle before you can decouple. So the realistic and pragmatic question is: how much untangling is worthwhile to achieve an equally worthwhile level of decoupling?

If you like what you've read, please SUBSCRIBE to the Interconnected email list. New posts will be delivered to your inbox (twice per week). Follow and interact with me on: Twitter, LinkedIn.

独角兽的纠缠:印度,中国,美国

在中美两国持续不断的科技冲突和竞争中,印度的角色正变得越来越有影响力——从与中国的边界冲突(可追溯到20世纪60年代),到禁止中国公司的所有apps,再到一些印度创业者承诺决不拿中国的钱作投资。与此同时,美国的各个科技巨头和专注科技的投资机构(亚马逊、Facebook、银湖、英特尔、红杉印度、沃尔玛、谷歌)正飞速的向印度科技行业注资,主要集中在Jio。

虽然印度最近的行动无疑在很多层面上继续验证“脱钩”这个大话题和趋势,但其实没有那么简单。如果更深入的看这三个国家的科技行业之间的资金流,就会发现有许多复杂的“纠缠”在背后。

为了探究“脱钩”与“纠缠”之间的关系,我们就看看美国和中国的科技大厂对印度“独角兽”(私有市场估值在10亿美元以上的科技公司)的企业战略投资。我只选择看“企业战略投资”是因为这类投资通常只在投资方和被投资的公司之间有长期的紧密业务结合的情况下才会发生,从而是强烈的“纠缠”信号。这并不是说风投、PE或主权财富基金的投资没有这种考虑,只是信号较弱。

当然,印度庞大而复杂的经济体也不仅仅是它的独角兽。我把重点放在独角兽上是因为它们往往是一个领先的指标,指向一个经济体的科技行业将走向何方。从个更现实的角度看,现在的印度独角兽也足够多,总共21家,所以可以做些分析了;五年前这种分析是做不到的。

分析“纠缠”

在分析对印度独角兽的战略投资之前,让我先说明一下研究信息的来源,这样大家可以清楚的知道这些数字是从哪里来的。印度独角兽来自CB Insights持续维护的全球独角兽名单。有关战略投资的信息来自CB Insights、Crunchbase和与这些公司有关的各种媒体报道。这篇文章中没有披露任何保密信息;谁都可以通过谷歌来找到这些数字和信息。

在21家印度科技独角兽中,超过一半的企业获得了中国科技公司的战略投资,约三分之一的企业获得了美国企业的类似投资,而还有三分之一的企业没有从这两个渠道获得资金。最有意思的是,有六家独角兽同时拿了美国和中国企业的战略投资,分别是:

- One97(拥有Paytm)-- 投资者:阿里巴巴/蚂蚁金服、英特尔

- Oyo -- 投资者:滴滴出行、Airbnb

- Snapdeal -- 投资者:阿里巴巴、英特尔、eBay

- Zomato -- 投资者:蚂蚁金服、苹果

- PolicyBazaar -- 投资者:腾讯、英特尔

- Udaan -- 投资者:腾讯、微软

因为中国科技巨头投了印度一半以上的独角兽,我觉的值得进一步细分这个群体。这张图列出了这些中国巨头都投了几家印度独角兽。

任何长期关注中国科技界的人都知道,整个格局的很大部份都瓜分了成“阿里系”和“腾讯系”,而这两系内的公司的互相竞争尤为激烈。滴滴出行的存在就是源于嘀嘀打车(腾讯系)和快的打车(阿里系)的合并,标志着这两大巨头在共享搭车行业的停战。

目前还没有迹象显示印度的科技界正以同样的方式被瓜分。我相信印度科技群体也会抵制这种现象发生,尤其考虑到当前的“大环境”。但有迹象表明,阿里和腾讯之间的竞争已经在印度的某些行业上演。

最好的例子就是Zomato(阿里系,因为蚂蚁金服做了战略投资)和Swiggy(腾讯和美团点评做了战略投资)在外卖送餐业务上的激烈竞争。印度最近的反华情绪直接影响了Zomato拿到蚂蚁金服的投资的能力,损伤了它对抗Swiggy的竞争力。值得注意的是,Uber今年1月把其印度的外卖送餐服务卖给了Zomato,获得9.99%的股份,因此Uber在这场竞争中也占有一席之地。别忘了,Uber早在2016年就把在中国业务卖给了滴滴出行,当时获得17.7%的股权,因此,它对滴滴在印度的所有投资活动都既得利益,虽然Uber没有直接出现在任何印度独角兽的筹资历史中。

各种纠缠还真不少呢。

谁的钱“更值钱”?

一个公司找投资不仅仅为了拿钱,更重要的是与投资方建立合作关系和从投资方的成功和失败中获得的宝贵的知识和经验,这些比金钱本身更有价值。钱的来源不同,它的价值也不一样。当一家公司在考虑拿不拿企业战略投资时,考虑谁的钱“更值钱”尤为重要。

那么从印度市场的角度看,是拿中国的钱“更值钱”还是美国的钱“更值钱”?有充分的理由证明,许多印度创业者认为中国的钱“更值钱”。

在以上图里这几个类别中,中国科技公司要么是在创新和技术方面的明显领先(比如电商),要么就是自身市场状况与印度更相似(比如物流/供应链和金融科技)。

我们仔细看看金融科技(FinTech)。虽然美国在FinTech方面一直有许多创新和发展,从支付和贷款到保险领域,但很多创新都是建立在围绕着信用卡的基础和用户行为上——这在中国和印度都不怎么存在。因此在中国,支付体验从脏脏的纸钱直接跳到了数字化现金,而其他金融产品也与数字化支付平台捆绑在一起,比如支付宝和微信支付。印度的互联网经济与10-15年前中国互联网的状况类似,印度走中国走出的这条路,同时加上自己的创新,以满足印度用户的需求和习惯,是非常合理的。但是,印度如果先引入像美国那样的信用卡系统,然后在此基础上进行科技创新和发展是不合理的。

图里的“其他”(Others)包括:教育科技、广告科技、游戏、外卖送餐和清洁能源。在所有这些领域里可以公平地说,对于一家希望在同一行业发展的印度公司来说,中国和美国各自的领先企业都具有竞争力和相当的价值。

为了专注和清晰起见,本文只分析了企业战略投资,有意没有看其他在印度很活跃的投资机构,比如软银(日本)、Temasek(新加坡)、Tiger Global、以及许多许多PE和风投基金,尽管它们都是“纠缠”其中的重要部分。就连巴菲特的Berkshire Hathaway也参与了这场游戏,在2018年投资3.6亿美元给印度最大的支付产品Paytm。因为这笔投资,Berkshire的利益也就与阿里/蚂蚁金服纠缠在一起。

就个人而言,我支持所有国家都在某种程度上达到“脱钩”。如果COVID-19给了大家任何启示,那就是在管理一个国家时,一定程度的自力更生和资源独立是绝对必要的,从而履行保护和照顾自己国民的基本职责。

但是,太多围绕“脱钩”的讨论都过于黑白分明了,在某种程度上脱离了技术和商业的现状。(我最近在“东南亚与太平洋光缆网”中就探讨了全球云计算的技术现状。)在看印度-中国-美国的三边关系时,显然在能“脱钩”之前有很多需要先解开的“纠缠”。因此,我们最应该问的,也是最务实的问题是:应该花多少资源解开多少程度的”纠缠”,才能达到必要程度的“脱钩”?

如果您喜欢所读的内容,请用email订阅加入“互联”。每周两次,新的文章将会直接送达您的邮箱。请在Twitter、LinkedIn上给个follow,与我交流互动!