One narrative that emerged when the global impact of COVID-19 became apparent was whether countries and companies who have been relying on China as their supply chain should leave or diversify. Since then, both the U.S. and Japan have been pushing their companies to leave China and manufacture at home or elsewhere -- the U.S. with rhetoric only for now, Japan with real money. (I’ve written about this a month ago as well, analyzing the various tradeoffs and arguing for a more prudent, less knee-jerk approach.)

The supply chain side narrative will take many months, if not years, to play out. Meanwhile, another side of China’s economy may have a more immediate impact in stabilizing the global economy towards an eventual recovery: the Chinese consumers.

China’s consumer base has been growing steadily, along with the rest of its economy, for the last four decades. More recently, this increase is occurring in the backdrop of a shrinking middle class in many OECD countries, including the U.S.

As China’s GDP falls by 6.8% in Q1 2020, the first ever contraction since China started keeping score, it will need its own consumers to spend. The world may need these same consumers to spend.

Will they?

Generational Attitude Towards Spending

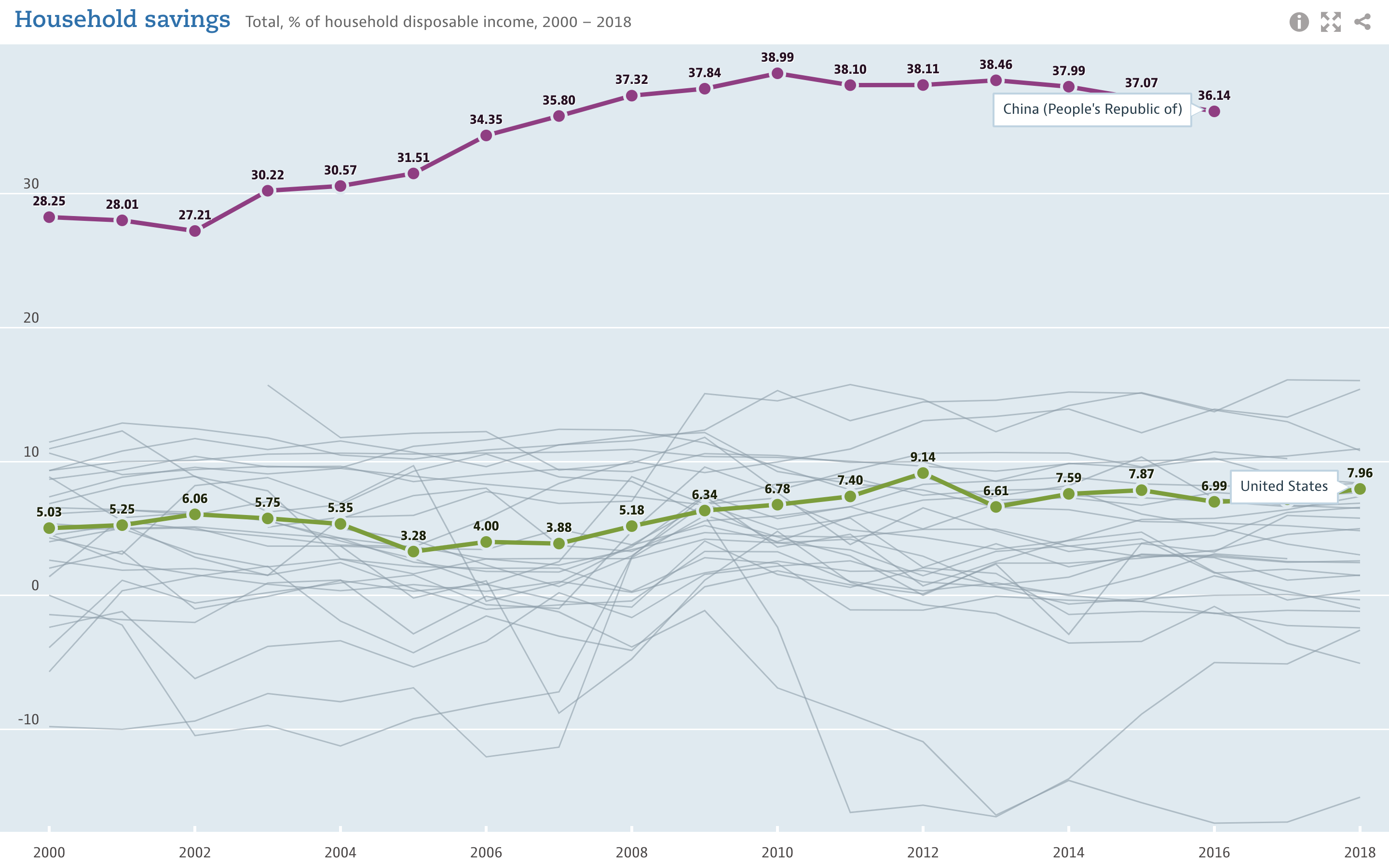

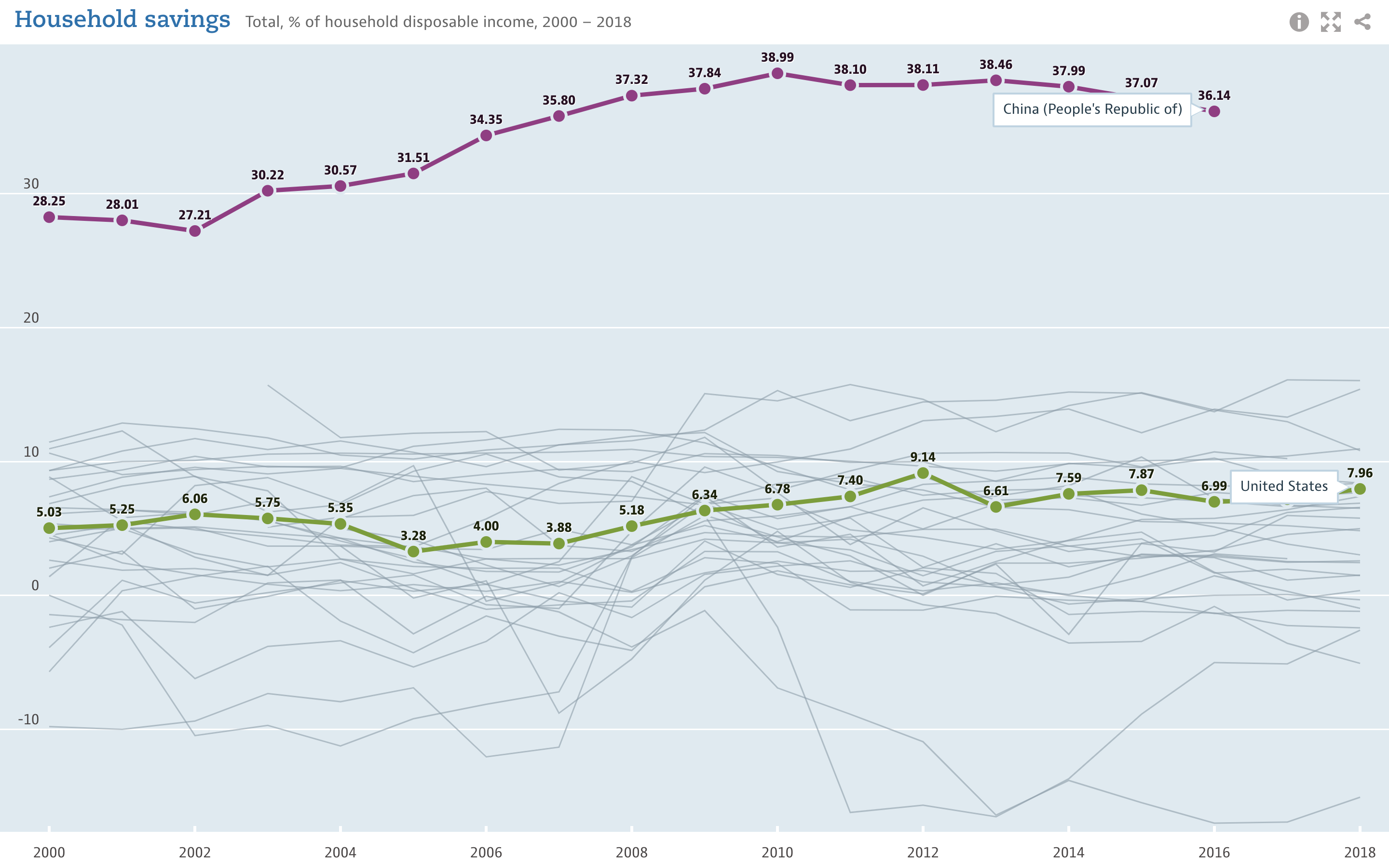

The general opinion of the Chinese middle class consumers is that their savings rate is quite high, about 5-times higher than their American counterparts.

But no consumer base or population is a monolith. To better understand the Chinese consumers, it helps to break them down into three generational buckets -- people born before 1970, between 1970 and 1990, and after 1990.

This breakdown may be too general for some of your likings. In fact, the common way ordinary Chinese chatter about generational divide is every five years -- born after 1985, 1990, 1995, etc. But for our purpose of analyzing and projecting broad consumer behaviors, three large buckets are sufficient. Excess precision can sometimes undermine analytical clarity.

Before 1970: This generation grew up poor, experienced a lot of political upheavals and economic crises, but also drove the initial stage of China’s opening and reform. This participation and timing created some wealthy outliers, like Jack Ma. Most of them, who simply played along, earned a so-called “xiao kang” life, which is a modest but comfortable living. This generation saves a lot, matching the stereotypical perception, and for good reasons. They are now heading into retirement, and many are shouldering the cost of taking care of their aging parents (in their 80s and 90s), helping their adult children with education or buying their first residential property, and saving for their own healthcare as they approach their golden years. They do travel, enjoy life from time to time, but rarely in extravagant ways.

Between 1970 and 1990: This group grew up less poor, more comfortable, but psychologically mindful of being poor, perhaps from seeing their parents’ experiences and hearing their stories. They are entering their prime earning age, starting young families, and facing the mounting cost of real estate, education, and upkeep of respectable living. This cost is especially acute for the ones living in first-tier cities. COVID-19 is likely the first large-scale economic crisis they’ve faced since China emerged from the 2008 financial crisis mostly unscathed. They are less frugal than the before-1970 crowd, but also circumspect and prudent when it comes to spending, due to their parents’ influence and the harsh reality of a highly competitive modern Chinese society.

After 1990: This bucket, as you might’ve guessed, was born into the most wealth and comfort. They are digital natives, well-traveled, self-assured, and optimistic. The “poor China” is just another page to gloss over in the history books. They have spending behaviors that most resemble the stereotypical American -- free-spirited with little savings. COVID-19 is also the first big economic crisis in their lifetime, but most important, they are also the first batch of university graduates and recent graduates heading into the most uncertain job market the world’s ever seen. Graduating during a crisis usually ends up coloring an entire generation’s outlook and attitude, regardless of the country; case in point is the college graduates in America during 09/11 and the 2008 financial crisis.

Admittedly, this categorization and analysis do not account for many factors, among which are the many poor people living in China today, mostly peasants in the rural regions or migrant workers on the outskirts of urban areas. Though to assess a topic as large as to whether consumption can help fuel a global economic recovery, the middle class is what’s relevant, as cold-hearted as that may be.

By overlaying these generational differences toward money and spending with the entire size of the Chinese middle class, roughly around 400 million people, we can glean some clues and signals into whether, where, and how much the Chinese consumers will spend after COVID-19.

Subtle Signs of Recovery

Already, there are signals, albeit subtle signals, that all three of these generations are continuing to spend in their own ways, even while the coronavirus is far from being controlled and cured.

Certain direct-to-consumer makeup brands, like Perfect Diary, are growing; this signal points to the after-1990 crowd. Online education companies are also growing; this signal points to the between-1970-and-1990 crowd, many of whom have young kids. Online grocery delivery is unsurprisingly also picking up growth; because this is an essential service, this signal likely points to all three buckets, but notably the before-1970 group, who may not be digital native, but are increasingly digital proficient in doing essential regular activities, like ordering grocery, directly from their smartphones.

Leading Chinese domestic players in these verticals -- direct-to-consumer brands, online education, and grocery delivery services -- are receiving new infusions of venture capital funding in the last few weeks. Chinese VCs voting with their capital is a noteworthy signal. It’s more telling than reports from the media, which have their own pre-baked narratives to drive, or online videos of malls either full or empty, especially when a big chunk of China’s commerce happens online. These deals are resulting in higher valuations for the companies, some almost doubling, so they are not cases of bargain hunting.

There is also a strong expectation from outside of China for Chinese consumers to spend on foreign goods and brands. Some European fashion brands have already been scrambling to launch on Alibaba’s Tmall, the main entry point to the Chinese market for foreign brands, when they saw demand in Europe plummet as COVID-19 spread there. As The Information’s reporting observed:

“If the pandemic severely hurts demand in the U.S., Japan, and Europe, global businesses may have to rely even more on the Chinese market.”

Thus far, there’s not enough information to show whether and why Chinese consumers are resuming their buying of foreign brands and goods, often considered a luxury, like they’ve been doing before.

It’s too early to conclude that any of these signals, though welcoming, indicate a trend. It’s also unrealistic to expect the entire Chinese middle class, assuming it doesn’t shrink, to return to its previous spending level. Furthermore, there are two big unknowns that determine to what extent the Chinese consumers will play a role in the global stabilization and recovery process: employment level and patriotic buying.

Employment Level: This unknown is shared by every country, but most acutely for the U.S. and China, given how interconnected these two economies are, even with the recent spate of trade wars. Broadly speaking, manufacturing in China makes up about 40% of its economy, and much of that is dependent on orders from non-Chinese companies. If foreign demand falls meaningfully or disappears intentionally, as the narrative to move supply chain hopes to validate, China may have to encourage spending to keep manufacturing, but also keep manufacturing to boost employment, so people have money to spend. It’s a vexing chicken or egg conundrum.

Some observers believe the Chinese people’s high savings rate will give them the cushion they need, without the type of direct cash stimulus that is happening in countries like the U.S. and Canada. That sadly isn’t the case for many of the after-1990 group, who are not habitual savers, least competitive in the jobs market right now, and may end up living off of their parents’ savings, which have many existing demands already.

Patriotic Buying: Even if we put on the rosiest of rose-colored glasses and see a Chinese middle class fully recovered and growing like before, where will their money flow to is a big question. This uncertainty is couched in the existing trend of retreat and animosity towards globalization, which has accelerated since the coronavirus outbreak. Nationalism is on the rise everywhere; people are looking for people to blame. This international finger-pointing is fueled by some national leaders, who would rather fan conspiracy theories to deflect blame than own up to their responsibilities. In both the U.S. and China, consumerism has always had a strong patriotic flavor. When Huawei was at the crosshair of the U.S.-China trade war, its smartphone sales received a big boost from Chinese consumers. Americans have done their fair share of patriotic buying in the last couple of decades, often beyond their means.

Xenophobia, disguised as public health measures, is on the rise everywhere. Professional observers may categorize these machinations as political chess games of the most cynical type, and they are not wrong. But ordinary consumers, regardless of nationality, don’t really care. Consumers buy what they need and what makes them feel good. The Chinese middle class was large before COVID-19 and may become the largest by spending capacity after COVID-19, depending on how other countries fare in this crisis. Whether we like to admit it or not, what will make the Chinese consumers “feel good” may determine which sector, market, or economy will recover.

If you like what you've read, please SUBSCRIBE to the Interconnected email list. New posts will be delivered to your inbox (twice per week). Follow and interact with me on: Twitter, LinkedIn.

中国消费者是不是全球经济复苏的关键?

当COVID-19的全球性影响显而易见的时候,一个热门话题就是国家和公司是否应该把产业链多元化,降低对中国生产的依赖。从那以后,美国和日本都在敦促自己的公司离开中国,转移到本国或其他地方制造产品。美国目前只是舆论,日本则是用真金白银在敦促行动。(我也在一个月前写过一篇文章,分析了离开中国产业链的各种利弊,主张谨慎对待,而不要随着舆论导向做出草率的决定。)

供应链这问题还需要数月,甚至数年的时间才会有结论。与此同时,中国经济的另一方面可能对稳定全球经济走向和最终复苏有更直接的影响:消费者。

在过去的40年里,中国的消费能力一直在稳步增长,与国家整体经济走向同步。最近十几年,这一增长发生在许多西方国家中产阶级萎缩的宏观趋势下,包括美国。

随着2020年第一季度中国生产总值(GDP)下降6.8%,也是自中国开始统计和公布生产总值后的首次下降,中国将需要自己的消费者花钱来得到经济复苏。整个世界也很可能需要这些中国消费者花钱。

他们会吗?

每代人对钱的态度

外界对中国中产阶级消费者的普遍看法是,他们的储蓄率很高,大约是美国中产的5倍。

但没有一个消费群体或人口是一个单面整体。为了更好地了解中国消费者,我将他们分为三代:1970年之前、1970年至1990年之间,和1990年之后出生的人。

你可能觉得这种分法太粗,不够细。这种看法也是有情可原。的确,中国老百姓在谈论这种话题时一般是每五年一分:85后、90后、95后等。但为了分析和预测广大消费者的宏观走向和行为,权衡分三组也该足够了。精确过度有时会破坏分析的清晰度。

1970年前:这一代人成长过程贫穷,经历过许多政治动荡和经济危机,但也推动了中国改革开放的初级阶段,创造了中国的第一批富豪异类,如马云。绝大部份人,只要在某种程度参与了这个大趋势,起码过上了小康生活,不算富裕但也算舒服。这一代人会省钱存钱,基本符合外界对中国消费者的粗旷看法。对这代人来说,多存钱的行为也是理由充分的。他们现在正走向退休年龄,许多人既承担着照顾八九十岁高龄父母的职责,也在资助成年子女教育或买房的费用,同时还要为自己未来的健康和医疗费用做储蓄。他们当然也会旅游,享受生活,但很少奢侈。

1970至1990年间:这一群体在成长过程没有那么贫穷,比较舒适,但贫穷这一概念离他们的思考并不远,也许是因为看到过父母的经历,听到过他们的故事。他们正迈进自己黄金收入年龄,开始成立小家庭,并面临着昂贵的房价、教育和维持体面生活的费用。对于生活在一线城市的人来说,这种经济压力尤其严重。新冠疫情也可能这一代人面临的第一次大规模经济危机,因为中国2008年金融危机中收到的影响总体不大。由于父母的影响和中国现代社会竞争激烈的严酷现实,他们虽然在花钱方面比生在1970年以前的人要松的多,但还是比较谨慎。

1990年后:可以想像,这一群体的成长过程最富有,最舒适。他们在数字化世界里长大,经常走遍世界各地,持有自信乐观的生活态度。“贫穷的中国”只是历史书中一个篇章而已。他们的消费习惯和态度与美国中产主流的最为相似:自由随意,也没有多少积蓄。冠状疫情也是他们有生以来的第一次重大经济危机,但更重要的是,这个群体里也包括步入极不稳定的全球就业市场的第一批大学毕业生和应届毕业生。在危机中毕业通常会影响到一整代人的观点和态度,无论是那个国家。911事件和2008年金融危机期间毕业的美国大学生就是个好例子。

诚然,这种分类和分析忽略了很多因素,其中包括当今生活在中国的许多穷人,大多数是农村人口或城市郊区的农民工。但是为了评估未来消费走向这种大话题,中产阶级才是最重要的,需要考虑的,尽管这种视角有些冷酷无情。

通过将这几代人对金钱和消费花销方面的差异与中国中产阶级(约4亿人)的整体规模相叠加,我们可以看到一些线索和信号,来分析中国消费者在疫情过后是否会花钱,会在哪些方面花多少钱。

微小的复苏迹象

已经有些微小的信号显示,这三代人都在以自己的方式和需求继续生活继续消费,尽管新冠疫情远未得到控制和治愈。

某些新型化妆品品牌,如完美日记(Perfect Diary),正在增长;这一信号指向1990年后的人群。在线教育公司的业务也在增长;这一信号指向1970年至1990年间出生的人群,其中许多人都有孩子。不奇怪,线上买菜送货服务也在增长;因为这是刚需,所以信号也许指向所有人,但值得注意的是生在1970年以前的群体,他们虽然没有在数字化世界中长大,但近几年与大势接轨,已经开始用手机处理日常生活中的许多事情,比如买菜购物。

过去几周里,在这几个行业里的中国国内领先企业也得到了新一轮风投资本。中国风投用真金白银投票是个值得注意的信号。要比媒体报道更有说服力,因为许多媒体有自己预先想讲的故事。也比各种网上流传的购物中心要么满,要么空的视频有说服力,因为中国一大部分商业活动都是在网上。这轮投资的估值都更高,有些公司的几乎翻了一番,所以它们并不是资本市场在“捡便宜”的案例。

其他国家也对中国消费者购买自己的商品和品牌抱有强烈的期望。早在疫情刚开始扩散到欧洲的时候,一些欧洲时尚品牌就已经开始争先恐后地在阿里的天猫上推出产品。正如硅谷科技媒体The Information的报告所述:

“如果疫情严重损害美国、日本和欧洲市场的内需,全球企业可能不得不更多地依赖中国市场。”

到目前为止,还没有足够的信息显示中国消费者是否开始恢复购买通常被视为奢侈品的外国品牌和商品。

虽然这些信号总体比较乐观,但现在下结论还为时过早。即使整个中国的中产阶级规模不缩小,指望所有人都百分之百回到以前的消费水平,也是不现实的。此外,有两个很大的未知数会决定中国消费者在全球稳定和复苏进程中将发挥多大的作用:就业水平和爱国消费。

就业水平:每个国家都对未来就业率的未知而苦恼,但最严重的是美国和中国,因为即使这两年的贸易战影响很大,这两个经济体仍是紧密相连。广义而言,中国制造业占其经济总量的40%左右,其中很大一部分依赖于非中国企业的订单。如果国外需求自然下降或有意消失,像转移供应链这种说法所期望的,中国可能不得不以鼓励消费的方式保住自己的制造业,但同时也要通过保住制造业来促进就业,这样人们才有钱消费。这是个极为复杂的,鸡生蛋蛋生鸡的难题。

一些观察人士认为,中国人民的高储蓄率将为他们提供足够的经济缓冲,从而不必像美国和加拿大等国家那样采取直接发现金的刺激措施。可惜的是,对于许多1990年后的群体来说,情况并非如此。他们没有习惯性储蓄,在就业市场上也最没有竞争力,最终可能要靠父母的储蓄为生,而父母的储蓄已经有许多现有的需求。

爱国消费:即使我们戴上最红的玫瑰色眼镜,假设中国中产阶级会完全恢复和继续增长,他们的钱会流向哪里是一个大问题。这种不确定性体现在对全球化的退却和敌意的大趋势中,而且自新冠疫情爆发以来,这种趋势开始加速。民族主义在世界各地都在抬头,许多人都在寻找他人谴责。一些国家领导人也在有意煽动这种情绪,宁愿鼓吹阴谋论来转移矛头,也不愿承认自己的失职。无论是在美国还是在中国,广大消费习惯的背后都具有强烈的爱国主义色彩。当华为变成中美贸易战的焦点时,其智能手机销售受到中国消费者的大力提振。在过去的十几年里,美国消费者在“爱国购买”方面也做很多“贡献”,往往超出了自己的经济能力。

伪装成公共卫生措施的仇外心理在各地都有。专业观察人士可能会将这些手法归类为最愤世嫉俗的政治游戏,他们也并没有错。但普通消费者并不在乎这些,无论是哪国人。消费者最终只会买他们需要的和让自己爽的东西。在疫情之前,中国的中产阶级很大。疫情过后,中国中产的消费能力可能会变成世界最大,这当然也取决于其他国家的恢复程度。不管我们是否愿意承认,什么东西会让中国消费者“爽”,可能会决定哪个行业、市场或经济体将复苏。

如果您喜欢所读的内容,请用email订阅加入“互联”。每周两次,新的文章将会直接送达您的邮箱。请在Twitter、LinkedIn上给个follow,与我交流互动!