I have been on the road lately, then promptly fell sick after returning home – a familiar pattern. The one silver lining about being stuck in a plane and being sick is that you are forced away from the stimulants of X/Twitter and “news”, while forced into stupor, inactivity, and much-needed reflection.

I have been reflecting on the past five-plus years of writing Interconnected, my humble personal platform on the Internet, dissecting and exploring the venn diagrams of technology, business, and geopolitics. Not a day goes by do I not see more interconnections, not less, between these broad disciplines, as do many others who write and think along these lines. That’s good! As we approach the Thanksgiving holiday here in America, I have a lot to be thankful for from the world and connections that opened up to me by writing Interconnected.

However, my writing has been inadequate and outright lazy in one important regard: repeatedly calling the US-China AI dynamic as a “race”, implying an end destination that does not exist and a zero-sum dynamic that does more harm than good. I have been lazily following how others describe things, even when most of them know less about the technology and less about what entrepreneurs and researchers in each respective country are actually doing than I do. As AI becomes the big wrapper in which everyone talks about technology, and as geopolitics becomes an even bigger wrapper that encompasses all technology trends, particularly AI, the way I talk about and describe US-China in AI must change. (I am not alone in realizing the inadequacy of “race”; others have had similar reflections.)

To fix this inadequacy, I have decided that going forward I will use the word “co-opetition” as the shorthand to capture everything I see in AI between the United States and China. It has the benefit of sounding like a fake word, which grabs attention, even though it has its own Wikipedia entry and is the title of a book. It is already used in the context of business and economics, but rarely in technology and geopolitics. It encapsulates what is really happening on the ground in AI, and what I believe will (and should) continue to happen for years to come, from three dimensions:

- Competition: the competition in AI model development and real-life applications and diffusion is fierce, both between American and Chinese labs, and among themselves! The cutthroat rivalries between OpenAI, Anthropic, DeepMind, and xAI are mirrored, if not more intense, between Alibaba, ByteDance, DeepSeek, and Moonshot. Since both markets are shut off from the other, this competition is expanding into other countries in the Middle East, Southeast Asia, and other regions, all trying to both leverage the best that American and Chinese labs have to offer, while exerting as much control and sovereignty as possible. Competition between companies and labs is real, and good! If the transformative nature of AI is real, then one single winner taking all the prizes is not healthy.

- Cooperation: underneath the hood, and under the breath of a lot of people doing the day-to-day work, there is still some cooperation between the US and China via academic research and open source. A recent report released by the Center for Security and Emerging Technology shows that between 2022-2024, 12% of the academic papers on AI being examined are produced by collaboration between researchers from the US and China. Is 12% a lot? That depends on who you ask. But cooperation, despite what you read and feel, is quantifiably not 0. Since the scope of this report covers the period before the “DeepSeek Moment” in early 2025, I eagerly await the next iteration of this report to see if the rapid growth of open weight AI from China is impacting cooperation in more positive or negative ways.

- Co-op

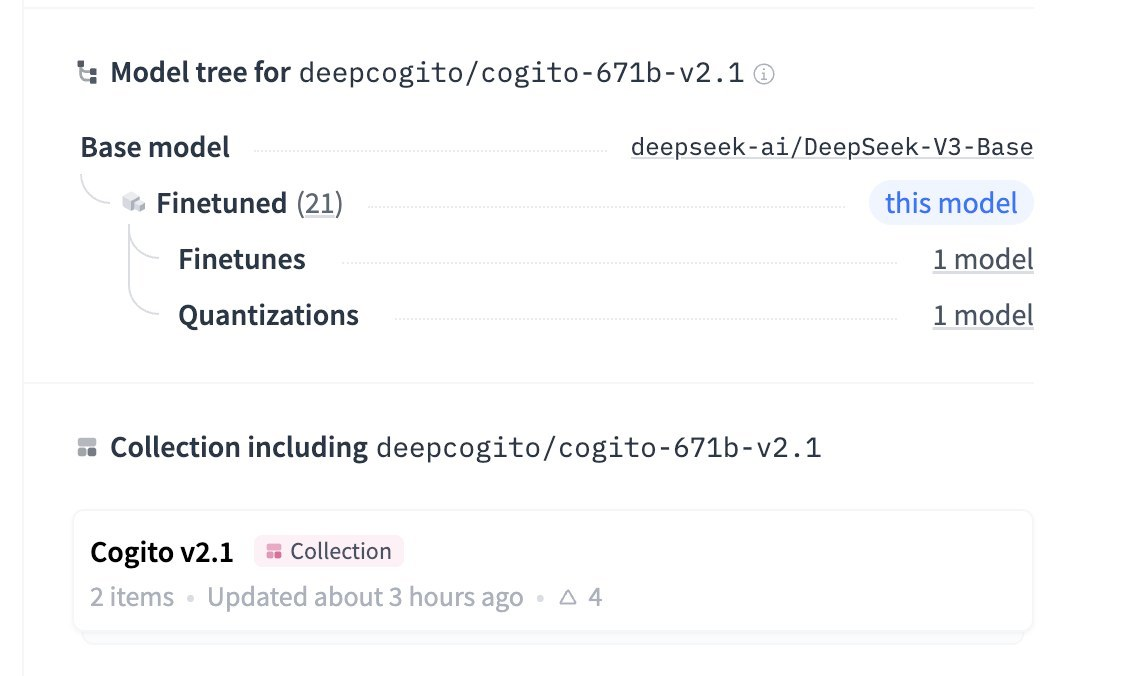

et: this third dimension is the most fascinating, even though it is most stretched from a linguistic point of view. “Co-opt” is what I was going for; let’s ignore that pesky little “e” in the middle. While the fierce competition and the low-key cooperation is happening, companies and labs from both sides are co-opting each other’s work, oftentimes without attribution or acknowledgement. During the first two years of the generative AI boom, many Chinese startups either directly leveraged Meta’s Llama model series to train their own (01.ai comes to mind) or the major cloud players immediately offered first-party support to attract users. This year, more open weight models from China are becoming the backbone of Silicon Valley startups, as most American labs are turning their backs on open source. Airbnb, Cursor, UiPath, and many others who don’t want to disclose their co-opting of Chinese models, given the toxicity of geopolitics. This is a pragmatic commercial decision in the face of sky-high valuation and market expectations. The latest and most comical example is a small startup called, Deep Cogito, claiming to have developed “the best open-weight LLM by a US company”, when its dependency tree revealed its origin as a fine-tuned derivative of DeepSeek V3.

Competition, cooperation, and co-opting each other’s output all live simultaneously in the “co-opetition” between the US and China.

When it comes to co-opting, or “stealing” as the more unscrupulous type likes to call it, this behavior is actually an essential element of open source norm. Chinese tech companies have been "co-opting" western open source (Linux, Android, MySQL/Postgres) to reduce dependency, improve profitability, and add customization for two-plus decades. American AI companies are now "co-opting" Chinese open source (DeepSeek, Qwen, Kimi) to reduce dependency, improve profitability, and add customization for their own customers. This is how open source works. No harm, no foul.

Repeatedly calling the US-China AI co-opetition a “race”, “new cold war”, “death match”, or pick your favorite blood-thirty, zero-sum metaphor gets you way more attention. The timeless aphorism – “it bleeds, it ledes” – never fails to explain the incentives that drive most newsrooms, editorial teams, and even newsletter writers, especially those who depend on open rate and paid subscriptions to make a living.

I am lucky (and thankful) that I don’t. That is one thing I will certainly celebrate this Thanksgiving – my intellectual independence. I don’t expect any mainstream media or bigger newsletter platforms to change the way they talk about US-China AI. I don’t expect governments to change either; a “race” has the nice side benefit of motivating a populace to do big things, even if the premise inaccurately portrays the ground truth. But I can and I will, if only to stay true to my own north star of intellectual rigor and honesty.

Long live US-China AI co-opetition.