I just touched down in Abu Dhabi a few hours ago. As I fight jetlag and get prepared for a week of on the ground fact-finding in the UAE, I will make this post short, but hopefully no less useful.

The new US National Security Strategy document was released last week. I dutifully read it during my 12-plus hour flight (as a good citizen does on long flights). Since its release, many smart and knowledgeable commentators have opined the document’s major elements, including notable changes in tone towards Europe and China. What I have noticed are a few passages that punctuate the interconnectedness, even explicitly intermingling, between technology and geopolitics.

In the Western Hemisphere section of the strategy, where the administration articulated a “Trump Corollary" to the Monroe Doctrine, these two passages jumped out at me:

“All our embassies must be aware of major business opportunities in their country, especially major government contracts. Every U.S. Government official that interacts with these countries should understand that part of their job is to help American companies compete and succeed.” (bold emphasis mine.)

“The terms of our agreements, especially with those countries that depend on us most and therefore over which we have the most leverage, must be sole-source contracts for our companies. At the same time, we should make every effort to push out foreign companies that build infrastructure in the region.” (bold emphasis mine)

The combination of these two passages signals that American diplomats stationed in the Western Hemisphere, and probably especially in Latin American countries, are now expected to have their ears to the ground for contracts and procurement opportunities where American companies should bid for (and hopefully win), while pushing out foreign companies seeking to do the same. These “foreign companies” are assuredly pointing to Chinese companies. Although when most people think of building infrastructure in developing countries, they see ports, airports, bridges, and roads – and they aren’t wrong – cloud data centers are also a key type of essential infrastructure.

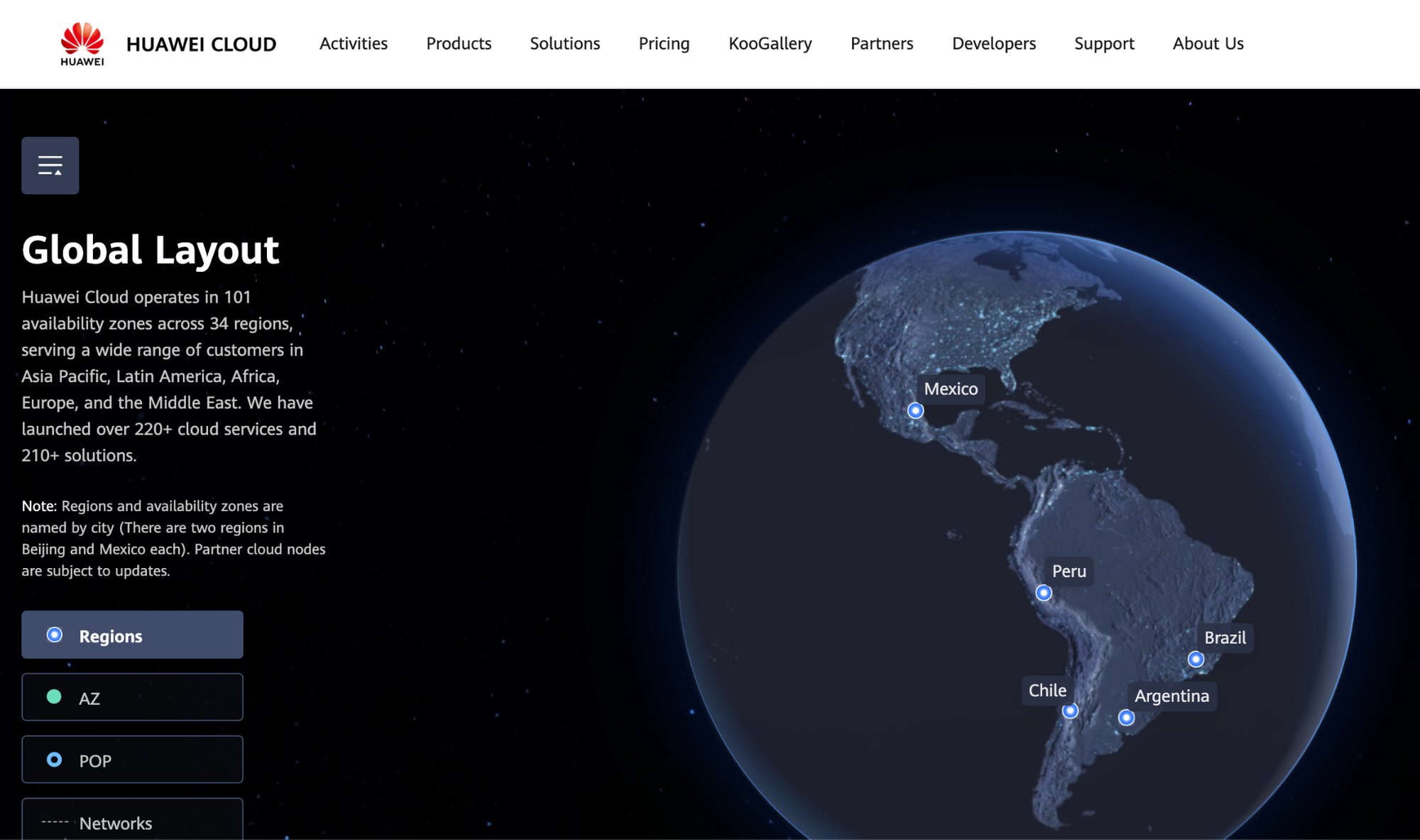

The last time I wrote about the geopolitics of the cloud was in July 2023. At the time, I jokingly opined about foreign service officers from the State Department becoming “presales” for AWS, Azure, and GCP. Looks like that is actually happening, and the joke is on me. In the same post, where I examined how the global cloud data center expansion was going, Latin America was a hotly contested region for both US and Chinese hyperscalers. In terms of the number of availability zones (the best way to quantify cloud infrastructure investment’s width and depth in my view), Huawei Cloud was in the lead with AZs in Brazil (2), Chile (2), Peru (2), Mexico (2), Argentina (1). The American hyperscaler with the deepest investment back then was Google, with presence in Brazil (3) and Chile (3).

To make sure my view is fresh, I checked the data center maps just before writing this post. Huawei Cloud has added two more AZs in Mexico and one more in Brazil since. Alibaba Cloud has opened its first data center in Mexico. Google has also opened its first cloud region in Mexico. It appears that Huawei Cloud has only furthered its lead, as it keeps investing and expanding deeper into the Western Hemisphere.

For a few years now, I have been writing about the notation of a “cloud war” – the competition between US hyperscalers and Chinese hyperscalers outside of their home market – as a next frontier of global technology confrontation. As AI becomes more widely diffused, and since most AI applications are served up as cloud services, where will the next cloud data centers be built and who is building them is becoming the key vector to look for in a US-China AI co-opetition. As the US government apparatus socializes and operationalizes the National Security Strategy, pushing out “foreign companies” like Huawei from building more cloud infrastructure in Latin America may become the strategy’s first big test.

This strategy does not stop with Latin America, of course, even though it was called out most explicitly in the region. Pushing the American tech stack abroad, and tasking every foreign and commercial service officer to not just do diplomacy but hunt for deals and contracts, is a core tenet of this strategy. On the other hand, the regime type of the country is no longer an important consideration when doing business, because business is business.

This worldview was articulated this passage in the Middle East section:

“The key to successful relations with the Middle East is accepting the region, its leaders, and its nations as they are while working together on areas of common interest.”

For anyone who stepped into foreign policy after 9/11, when the global war on terror was the overarching strategy, and democracy promotion was the thread that binds and justifies all foreign policy actions, this passage will feel jarring. Back then, regime change, spreading the virtues of voting, and conducting election monitoring was the bar of progress. With the publication of this National Security Strategy, that era is officially over. If you are an aspiring and ambitious young foreign policy hand, knowing how foreign governments' do IT procurement will put you on a faster path to success than knowing how to administer local elections, as we as a country move on from pushing for more voting to pushing for more selling.