Ever since OpenAI released its o1 model last September (only 7 months ago!), the AI world has been progressing at a feverish pace into the reasoning model paradigm. The pace has been fast and furious, and so has the volume of the noise obscuring the signals, as jargon flies everywhere.

I have struggled with it myself (and won’t blame my newborn on this one), and see others struggle with it, too. The one thing I took away from having gone to law school years ago is reasoning by analogy. A bad analogy can gloss over a lot of truths. A good analogy, however, is relatable, can illuminate understanding, and keep things simple without oversimplification.

In my attempt to clarify the continuum of pre-training, test-time compute, and inference—where the frontier of AI models is headed—I’ve been using an analogy almost every ordinary person can relate to: taking an exam.

AI Takes an Exam

Pre-training is cramming for an exam. Study, memorize, and structure all the information you can, so on exam day, you can recall information as quickly as possible with the highest accuracy possible. This exam would be a classic standardized test – time-bound, no notes, recall whatever is in your brain after cramming (or pre-training) to answer the questions.

A little over two years ago, when we all first experienced generative AI using ChatGPT, that was OpenAI’s model, having crammed all the information it could get its hands on at the time, bracing for the exam questions from its users. Nothing more, nothing less.

Every model that has emerged since then that immediately spits out an answer after a question was asked can be categorized into this cohort of pre-trained but non-reasoning models: GPT before o1, all Llama models, Gemini before deep research, Claude before computer use, DeepSeek V3 (not R1), Alibaba Qwen (not QwQ), etc.

Test-time compute, the term that gets thrown around a lot to describe how reasoning model differs, is basically a model taking an open-book or a take-home exam. To answer the exam questions you can “think” and reference new information (or old information you want to double check with) before answering the question. The model was still pre-trained; some cramming still had to happen before exam day (or “test-time”). And the exam is still somewhat time-bound. You can’t take forever to answer the question, but you get more time than the classic, closed-book exam.

When I tried out the Manus AI agent and compared with GPT 4.5 and Gemini in deep research mode to analyze a company (CyberArk), watching Manus read pages on the internet and SEC filings was literally like watching a person take an open-book, take-home exam. I imagine if OpenAI, or Google, or other AI agent makers show the process of its models "reasoning", it’ll feel similar.

Manus takes an open-book exam on CyberArk

The relevant cohort of models that do open-book exams: OpenAI’s o1 and o3 series, Gemini’s Deep Research and Flash Thinking, Claude with “extended thinking” or computer use mode, DeepSeek R1, Alibaba’s QwQ, etc.

As you can see, most leading AI model shops will produce both types of models – reasoning and non-reasoning. They serve different purposes. Non-reasoning models are often used to improve reasoning models.

Most frontier models in the future will be reasoning models with test-time compute. Why? Because they best match real world use cases and needs, just like the human exam taking experiences. Very few people believe that standardized exams – SAT, gaokao, the bar, CFA certification – is a good representation of what is required to succeed in the real world. We just put up with it due to lack of a better alternative to simulate a level playing field. Real work with real value, at least most knowledge work, is akin to a giant open-book exam with the time-limit set by your boss, your customer or your competitor.

Inference is producing the answer to an exam question. Non-reasoning models go from pre-training (cramming) straight to inference (answering). Reasoning models take an extra time-test compute step in the middle with the goal of producing better answers.

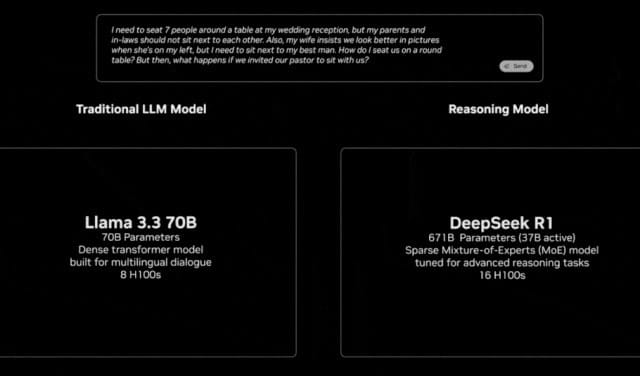

At Nvidia’s GTC conference earlier this week, Jensen Huang showed a comparison of exactly this dynamic on the keynote stage, between Llama (non-reasoning) and R1 (reasoning) when answering the same question.

While this inference stage may be the simplest to analogize, it is by no means technically easy. Delivering a coherent answer that fits the situation and needs is yet another knob that the AI models can turn to make themselves more useful. Claude’s model embodies this complexity quite well by presenting four choices – normal, concise, explanatory, formal – for the users to choose when receiving a response.

Much like human exams, some questions, like essay questions, want you to elaborate and share all the details you know. Other questions, like multiple choice, just want a concise, pithy response.

Time Limit and Benchmarking

A few more words to extend the exam analogy along two other directions: time limit and benchmarking.

Even though test-time compute is all the rage right now, AI still cannot take forever to answer questions, just like how an open-book exam still has a time limit. The tradeoff between answer quality and accuracy versus the time it takes to get to that answer will be the linchpin to how much AI can proliferate and be adopted in the real world. Getting this tradeoff right goes to the heart of user experience, where the speed of thinking and delivering quality answers still matters, which means the speed of computation is still an important factor.

Benchmarking, which every new AI model inevitably excels in when it is released, is kind of like knowing the questions ahead of taking the exam. This does not mean that scoring high on benchmarks is useless information. After all, just because you know the question in advance does not mean you can answer the question. But knowing the questions in advance lends itself to fine-tuning models to score well on certain benchmarks. That said, it’s rarely possible to excel at all known benchmarks because everything is a tradeoff. So whenever you see an impressive benchmark score, put it in context, view it appropriately, and be aware that the practice of “benchmarketing” is as old as time. The AI industry is not immune to it.

To AI academics and researchers who are in the weeds of building frontier AI models, I hope my human exam-taking analogies do not gloss over too many salient details, and they illuminate more than they obscure.

For people who have a stake in AI – investors, policymakers, enterprise adopters, everyday users – but don’t work intimately on the training or development of AI models and find all the jargon confusing, I hope my analogy can serve as a solid grounding that you can recall and relate to in your own life, every time the discussion gets too noisy.

Just remember, whenever you interact with an AI system, it is taking either a closed-book exam (non-reasoning model) or an open-book exam (reasoning model). The exam questions are your requests. No more, no less.