I spent the last week in the United Arab Emirates (UAE) on a fact finding trip focused on the country’s AI ambition. I was part of an American delegation among Washington, DC think tankers, which brought back fond memories of when I was an inside the beltway person myself when serving in the Obama administration.

Although I have developed a notion that the Middle East is fast becoming a pivotal player in the US-China AI co-opetition a year ago, it was done mostly through reading, observing from afar, and intuiting from broad technology and geopolitical fundamentals. Up until last week, I had never been to the UAE, a key driver in the region’s AI wave, nor any other part of the gulf region. On this trip, we were able to meet with key decision makers from almost all the relevant institutions in its AI ecosystem, from capital and finance, to government agencies, to tech companies and universities.

Narratives often move markets and policies temporarily, but the ground truth is what’s valuable and enduring. And you can’t find any ground truth unless you are on the ground! This post is my first attempt at unpacking some of the ground truth I gathered, and what it all means for the future of AI globally.

(A lengthy but important disclosure: this trip was sponsored by the UAE Embassy, meaning they paid for our flights, hotels, most meals, and helped arrange all the meetings. The flight was comfortable and the hotels were very fancy, though our schedule was also so packed on some days that we had 10 minutes to eat breakfast, skipped lunch, and barely had time to go to the bathroom. This generosity should not go unrecognized and unappreciated. But at no point during the trip did I feel pressured or expected to “write something nice” about my experience, or write anything at all. Most people on the trip did not know I have a newsletter with more than 10,000 subscribers. When our official agenda was concluded on each day, I was left alone to my own devices to explore the country however I preferred without any restrictions. All meetings were conducted under Chatham House rule, so whatever insight I share in this post and future posts about this trip will not be attributed to anyone or any institution. It is an aggregation based on my notes and interpretations, so any mistake I make is mine and mine alone.

I prefer to issue any disclosure upfront, so you have it in your mind as you read, as opposed to hiding them at the end of an article in fine print, as is often the case, when few readers are paying attention. This is done to reinforce the integrity and accountability of everything you read on the Interconnected newsletter. It doesn’t mean I get everything right, but if I did get something wrong, they are honest mistakes and not committed under undue influence or conflict of interest.)

Not Switzerland

I intentionally did not do much prep before the trip, deciding to show up as a blank slate, be a sponge, and absorb everything that is presented to me, then sort out facts from fiction independently on my own. The only “prep” I did, if you can even call it that, was watch the movie, “Fast and Furious 7”, on my plane ride to the UAE. This is the one with that dramatic scene, where Vin Diesel drove a sports car through not one but two glass skyscrapers in Abu Dhabi.

As luck would have it, our hotel on the first night was right next to those glass skyscrapers, the Etihad Towers. Standing on the balcony of my room, I could see Vin Diesel in that brakeless sports car flying straight to my room – a fitting mental image for my week ahead.

The pace of building is literally fast and furious, both in Abu Dhabi and Dubai. One factoid that stuck out in my head was that there are 1.5 million construction workers in the UAE, out of a total population of 10 million. In other words, 15% of the population wakes up every morning building…something! Skyscrapers, hotels, convention centers, a third palm-shaped artificial island for mansions and resorts, and more.

A solid portion of that construction capacity is also devoted to an around-the-clock effort to build AI infrastructure, particularly Stargate UAE. That’s the 1 gigawatt data center being built in partnership with OpenAI, as part of a 5 gigawatt mega data center project partnership between the US and the UAE. When it is all said and done, the entire campus is designed to house the most advanced GPUs to serve up the most advanced AI models for local and American companies. It is projected to be the size of nine (9) Monacos. It is one of many Stargates that OpenAI has announced around the world, from Norway to Argentina, but it is the one that has made the most progress, except for the first Stargate in Abilene, Texas. Most important, on a global strategic level, it is a physical manifestation of how the UAE, a critical “swing vote” in the US-China AI co-opetition, has voted this time: Team USA.

The UAE is often seen under a skeptical lens in the context of the grander struggle between the US and China, awkwardly and uncomfortably sandwiched in the middle, and rarely talked about on its own terms. It has been treated as a "Switzerland", even though it emphatically does not want to be a “Switzerland”, a point of frustration that we heard repeatedly during our trip.

Switzerland, after all, is a symbol of neutrality. A neutral party does not vote; it abstains. The UAE does vote, and has voted with its labor force, seemingly unlimited capital, and a point of view. To reduce the skepticism and suspicion, some organizations have preemptively asked its engineers to not use Chinese open weight models, a step that surprised me as above and beyond in order to make the American side feel better. Others have described the UAE’s AI infrastructure buildout as a “51st state” extension of America’s global AI capacity. Even a football analogy was used to drive the same message: if this big nation AI competition is a Super Bowl of sorts and the US is the quarterback, then the UAE wants to be the fast (and furious) wide receiver, sprinting down the sideline and calling for the ball to score a touchdown.

This is a well-curated analogy, of course, designed to be relatable to an American delegation. A football analogy would fall on deaf ears for a Chinese audience. But the larger point was clear: the UAE has voted in favor of the US when it comes to AI, it does not want to be seen as Switzerland, and it needs to make this big bet work! Now that the vote has been cast, the UAE steps into the implementation and delivery stage, just like the rest of the AI industrial complex.

Some elements of the UAE’s AI infrastructure offering are undoubtedly appealing and directly counter the challenges in the US. Energy is abundant; the case is opposite in the US. A sizable foreign construction workforce is ready and can be boosted with a generous workers visa scheme to attract more from the so-called Global South. Meanwhile, the US is aggressively deporting migrant workers without a holistic fix on its immigration system.

One big question I had coming into this trip was, from a technical point of view, does it make sense for American hyperscalers to reserve GPU capacity from the UAE to run inference workloads servicing that part of the world, as a regional “token factory” of sorts? Considering that the undersea cable latency between the UAE and major population centers in India and Pakistan is less than 30 milliseconds (aka very fast), the speed is there. Local technology outfits are also investing in its engineering team to build rock solid multi-tenant solutions – a table stakes feature in all the hyperscale clouds that is easier said than done. If both physical and virtual isolations can be delivered with multi-tenant support, I can see American hyperscalers pushing more AI workloads into this gulf state. This push may accelerate when domestically in the US building data centers is becoming more challenging, due to a lack of reliable and competent labor force, readily available energy, and growing political scrutiny heading into the mid-term elections.

Other ideas that are filling the UAE AI story are a bit half-baked. One such example is “digital embassy”, where other countries will “own” and run their sovereign AI workload in a UAE data center like Stargate. This property ownership will be similar to a real embassy, where the land where the embassy sits on belongs to the foreign country running that embassy. It is a nice idea, and would certainly boost data center utilization, but runs counter to the logic of having sovereign AI in the first place. If a country indeed believes that AI is the most important technological transformation of all time, it would want to build its own infrastructure within its own borders sooner or later. If a country is not AGI-pilled, then such a “digital embassy” offering would not be attractive. If a country needs a temporary boost of sovereign AI capacity, while waiting for its own construction to complete – a scenario that was presented to us during one of our meetings to describe a “digital embassy” use case – then this offering is but a temporary stopgap, not a sustainable way to consume compute. In short, I will keep an open mind, but remain on the sidelines of this “digital embassy” idea until there is more proof in the pudding.

Pragmatic Like Singapore

In order for a swing vote to keep its leverage, not be Switzerland, and maintain relevance, it must, in a sense, keep swinging. Otherwise, sooner or later, it will be taken for granted by whichever large nation won its vote.

This approach to techno-geopolitics is ultimately an exercise in pragmatism – a word that keeps popping into my head throughout the trip. It is an approach typical of small countries with big ambitions, aspiring to punch above its weight class. The UAE’s full-throated embrace of AI is actually an expression of this pragmatism, not some pie in the sky techno-idealism.

For a country of merely 10 million people, roughly the size of Michigan the American state or Nanjing the Chinese city in terms of population, if this AI thing boosts productivity or drives efficiency by 40% or 50%, it would be as if the UAE all of a sudden has 4 or 5 million extra people! In this case, the law of small numbers dictates a high level of conviction in the multiplier effect of technology. For the UAE, and dare I say most small countries with big plans, betting on AI is not a question of “why”, but “why not”. What do you have to lose?

In many ways, the UAE’s pragmatism resembles another small yet ambitious country: Singapore. As we were taken around Abu Dhabi and Dubai, I saw flashes of Singapore, from gleaming towers and clean streets, to an emphasis on westerner-friendly services where everyone spoke English. It is not a coincidence either that Singapore has become a dense node of cloud compute capacity, serving a large swath of the APAC region. The UAE is doing exactly that for its corner of the world with Stargate.

In classic pragmatic fashion, these two states study each other closely. Both the president of UAE, Sheikh Mohamed bin Zayed Al Nahyan, and its prime minister, Sheikh Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum, have either publicly acknowledged Singapore's development journey as “a distinguished model” or honored its founding father, Lee Kuan Yew. Staying true to its pragmatic genes, Singapore is also studying the UAE model closely, especially in AI. After the UAE became the first country in the world to name a Chief AI Minister in 2017, Singapore named its own in 2023.

Another hallmark of pragmatism is that you have to work with everyone, in one shape or another. Yes, the UAE has voted in favor of the US in the AI realm. But China is still the desert country’s largest trading partner. And as a desert country, where few things grow, it has to import just about everything. None of the delicious meals we enjoyed from our hotels or at dinner outings were farm to table. They were farm to fridge to shipping containers across the ocean to another fridge to eventually our table.

So trade and commerce has to continue with China. Pragmatism demands it. Ripping out Chinese technologies in critical infrastructure and AI data centers in order to procure more advanced American or western ones will also continue. Pragmatism demands it. As for less critical, less strategic technology, like the Hikvision cameras I saw dotted above all the streets I walked in Dubai? They will keep operating to keep the streets safe, until the definition of "critical" or “strategic” changes. Pragmatism demands flexibility above all.

Inclusivity by Chopsticks

It is easy to get tunnel-visioned into the AI boom and its usual abstractions – 5GW here, more chips there, LLMs and agents everywhere. While we all wait for and build towards a possible AI-native future, what happens on a day-to-day basis is less abstract and more human.

Whether it is the UAE or elsewhere, a country needs to attract both more lower-end workers to construct and higher-skilled talent to make good use of what is being constructed. And to make it all sustainable, everyone has to live among each other in peace, safety, and relative comfort. Achieving that level of talent density necessitates human “inclusivity”, which has become a bizarrely toxic and divisive notion in recent years.

How does the UAE plan to achieve both talent density and inclusivity in its own way? A phrase we heard a few times during our trip was an “inclusive representative tribal system”. In other words: everyone is welcome, come as you are, as long as you live within the boundaries and traditions of the Emirati culture.

I don’t pretend to have any knowledge or insight into the Emirati tradition, identity, or historical tribal system. I also don’t pretend to know how it feels to live within that tradition as either an investment manager from London or an Uber driver from Pakistan, both of whom I met on this trip. But it sure sounds nice! It also sounds like something you see in a PowerPoint deck or brochure.

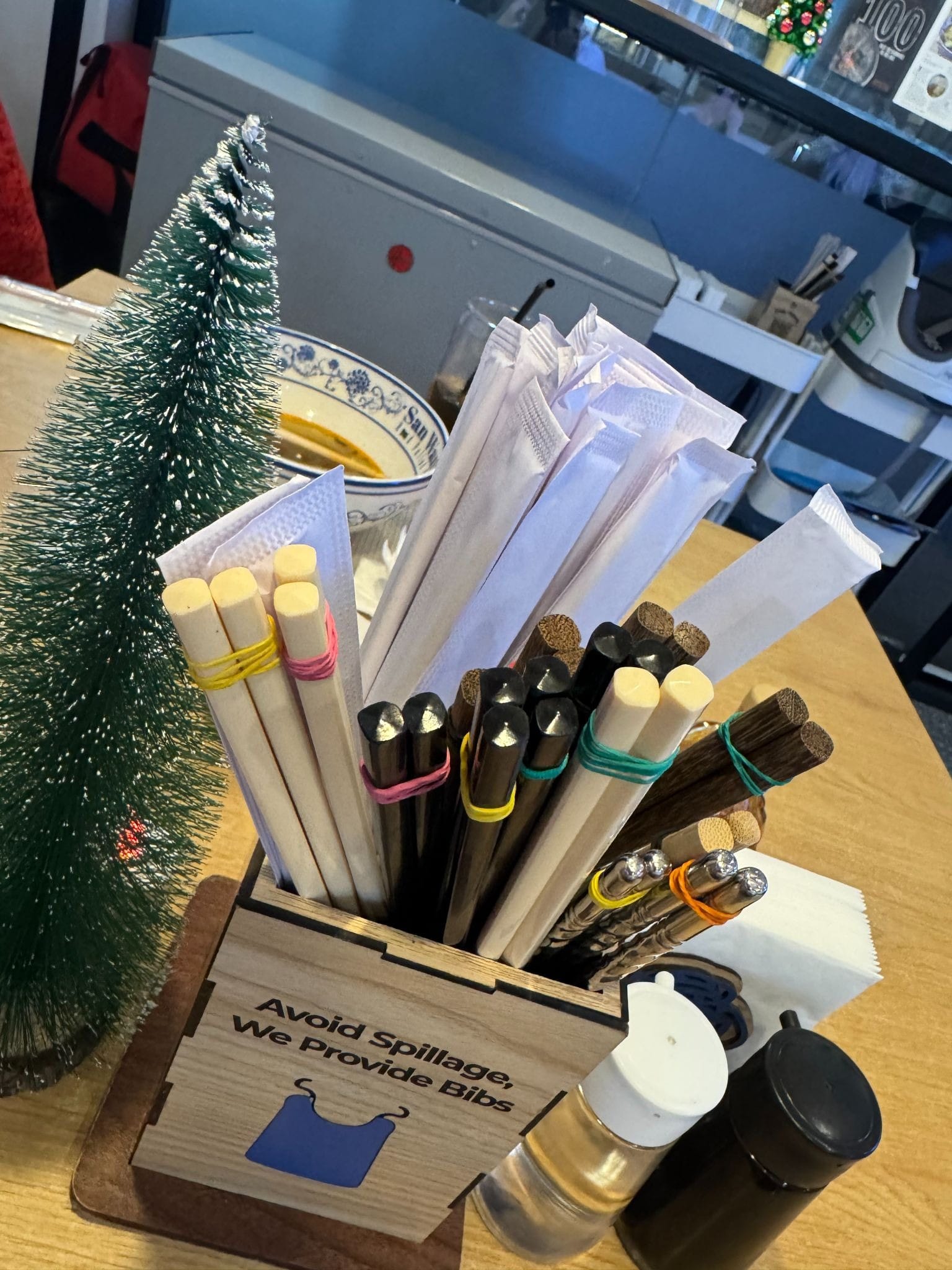

How do you find ground truth on this “inclusive representative tribal system”? Luckily, I got a small taste of it during one of my free evenings in Dubai, when I went out on my own to a hand-pulled noodle restaurant, called San Wan Noodles, at the recommendation of a fellow delegation member. After finding this no-frills, modest establishment, tucked away at the bottom of a tall apartment building after a row of other restaurants, I devoured a big bowl of beef noodle soup and a plate of chicken dumplings. As I was catching my breath after ten minutes of non-stop eating, I discovered that the chopsticks box on my table had not one, not two, but five different types of chopsticks!

For the uninitiated, chopsticks come in many different materials and shapes. Some prefer them pointy and made out of bamboo. Others prefer them round and made out of plastic or ivory. The Koreans specifically prefer their chopsticks slightly round and made out of metal. Having been to hundreds of restaurants in many countries over my life, where chopsticks were the main utensil, I have only seen chopsticks offered in one, at most two, types.

Until Dubai, I have never seen a place that offered this many types of chopsticks all at once for the customer to choose from. As a lifelong chopsticks user, it doesn’t get more inclusive than this. And I doubt this modest restaurant received a decree from the Crown Prince to be more inclusive with its chopsticks offering. It was organic.

Regardless of what misconceptions or fantasies you have about the UAE, with or without AI, the world could use more tolerance, more inclusivity, and less judgement. This small restaurant in Dubai, with its diverse and inclusive chopsticks, may just be the best embodiment of that spirit.